Introduction

The Role of Material Selection in Mechanical Design

Material selection in mechanical design is a cornerstone of mechanical design, directly influencing performance, cost efficiency, and environmental sustainability. Engineers must balance mechanical properties—such as strength, thermal conductivity, and fatigue resistance—with economic constraints and lifecycle environmental impacts. A suboptimal choice can lead to premature failure, inflated costs, or excessive carbon footprints, underscoring the need for systematic evaluation.

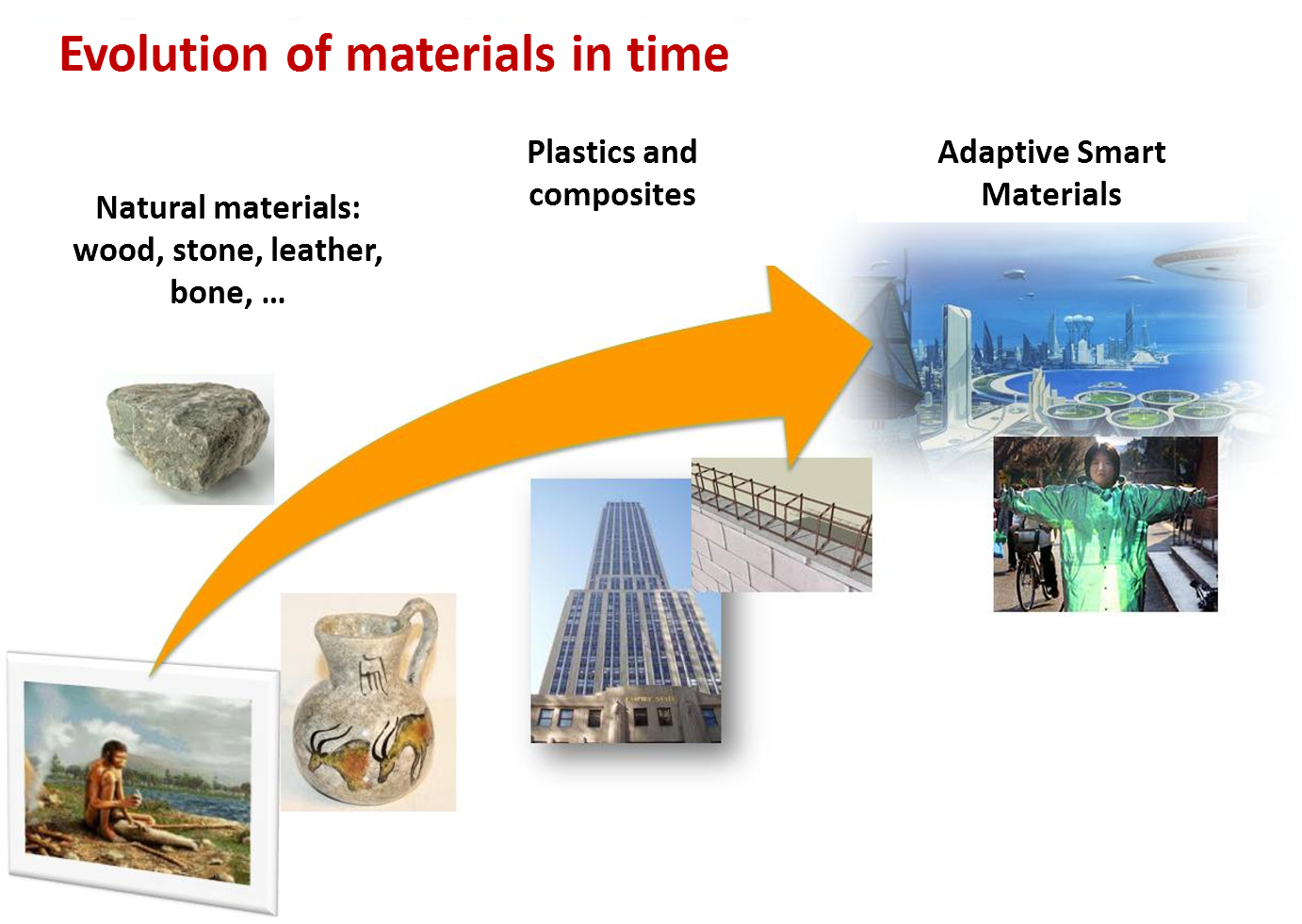

Historical Perspective & Modern Challenges

The evolution of materials in engineering spans millennia, from bronze and iron in ancient tools to advanced composites and smart materials today. The Industrial Revolution marked a turning point with mass-produced steel, but modern designers face unprecedented complexity. Innovations like lightweight alloys and biodegradable polymers introduce new opportunities, yet challenges such as stricter environmental regulations, global supply chain volatility, and competing performance demands require designers to navigate intricate trade-offs. Rising emphasis on circular economies further complicates decisions, as recycling infrastructure and material degradation behaviors become critical factors.

Fundamental Principles of Material Selection

Defining Material Selection

Material selection in mechanical design refers to the systematic process of choosing materials that align with a product’s functional requirements, manufacturability, cost targets, and sustainability goals. It involves evaluating mechanical properties—such as thermal conductivity and fatigue resistance—alongside non-mechanical factors like corrosion behavior, weight, and compliance with industry standards. In product development, this process ensures that materials meet performance benchmarks under operational stresses while addressing lifecycle considerations, such as carbon footprint and end-of-life recyclability.

Key factors driving material selection include:

- Mechanical performance: Strength, ductility, and wear resistance under load.

- Economic viability: Balancing raw material costs, processing expenses, and supply chain volatility.

- Environmental impact: Prioritizing materials with lower emissions, compatibility with recycling infrastructure, and renewable sourcing.

Fundamental Principles of Material Selection

Key Material Properties and Their Impact

- Mechanical Properties

- Strength: Ability to withstand applied loads without deformation or failure.

Example: Titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) offers tensile strength of ~950 MPa, making it ideal for aerospace components. - Stiffness: Resistance to elastic deformation under stress.

Example: Aluminum 6061-T6 has a Young’s modulus of 68.9 GPa, balancing rigidity and lightweight design. - Ductility: Capacity to deform plastically before fracture.

Example: Copper (99.9% pure) exhibits ~50% elongation at break, essential for electrical wiring. - Toughness: Energy absorption before fracture.

Example: High-toughness steel (AISI 4340) with 100 MPa√m fracture toughness resists impact in automotive chassis. - Fatigue Behavior: Resistance to cyclic loading.

Example: Aluminum 7075-T6 has a fatigue limit of ~160 MPa, critical for aircraft landing gear.

- Strength: Ability to withstand applied loads without deformation or failure.

- Thermal & Chemical Properties

- Thermal Conductivity: Heat transfer efficiency.

Example: Copper (385 W/m·K) is used in heat exchangers for rapid thermal dissipation. - Thermal Expansion: Dimensional change with temperature.

Example: Invar (Fe-Ni alloy) has a near-zero coefficient (1.2×10⁻⁶/°C), ideal for precision instruments. - Corrosion Resistance: Degradation resistance in harsh environments.

Example: Stainless steel 316 (16% Cr, 10% Ni) withstands saltwater exposure in marine applications.

- Thermal Conductivity: Heat transfer efficiency.

- Emerging Considerations

- Recyclability: Compatibility with recycling processes.

Example: Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) achieves 90% recyclability rates in packaging. - Environmental Impact: Lifecycle carbon footprint.

Example: Biodegradable polylactic acid (PLA) decomposes in 6–12 months under industrial composting.

- Recyclability: Compatibility with recycling processes.

Specification Examples

- Recycled Aluminum: 6061-T6 recycled alloy reduces energy use by 95% vs. virgin production.

- Carbon Fiber: High strength-to-weight ratio (3.5 GPa tensile) but emits 20–30 kg CO₂/kg during production.

Overview of Material Families

Material selection for mechanical design requires a complex process that depends on comprehending the distinct properties of different material families. The selection of materials from metal, polymer, ceramic, composite, and bio-based families determines performance levels while affecting both cost and sustainability outcomes.

Metal

Material selection for mechanical design often begins with metals due to their well-established performance metrics and versatility in engineering applications. For instance, mild steel is a staple in structural applications because it offers tensile strengths in the range of 400–550 MPa, Young’s modulus of approximately 210 GPa, and a density of around 7850 kg/m³, making it ideal for components that must withstand significant loads while maintaining ductility and toughness.

In contrast, aluminum alloys—such as the widely used 6061-T6—provide tensile strengths of about 290–310 MPa, a considerably lower modulus of roughly 69 GPa, and a density near 2700 kg/m³, which is crucial for designs where weight reduction is a priority without sacrificing sufficient strength. Moreover, high-performance metals like titanium alloys, exemplified by Ti-6Al-4V, push the envelope further by combining tensile strengths of approximately 800–900 MPa, a modulus around 110 GPa, and a density close to 4500 kg/m³; these properties make titanium alloys indispensable in aerospace and biomedical applications where the best strength-to-weight ratio is required. S

uch quantitative data on material properties not only aids engineers in making informed decisions during the material selection for mechanical design but also provides a basis for optimizing performance indices—like specific strength (tensile strength/density) and specific modulus (Young’s modulus/density)—to meet the rigorous demands of modern mechanical design projects.

Polymer

Material selection for mechanical design using polymers offers a versatile and lightweight alternative to traditional materials, providing a unique balance of performance and processability. High-performance polymers like polyetheretherketone (PEEK) are often chosen when durability and thermal stability are critical; PEEK typically exhibits tensile strengths of approximately 90–100 MPa, Young’s modulus around 3.6 GPa, and a density near 1300 kg/m³, making it suitable for high-stress applications that operate at elevated temperatures.

In contrast, Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) is widely used for its ease of processing and cost efficiency, offering tensile strengths in the range of 40–50 MPa, Young’s modulus of roughly 2–2.5 GPa, and a density between 1040 and 1100 kg/m³, which makes it ideal for non-critical structural components where impact resistance and moldability are prioritized.

Additionally, Nylon 6,6 is frequently employed in mechanical design for components like gears and bearings due to its moderate tensile strength of 75–85 MPa, Young’s modulus around 2.5–3 GPa, and a density of approximately 1150 kg/m³, ensuring a good balance of toughness and flexibility. These detailed specifications not only highlight the inherent material properties that influence performance and longevity but also underscore how polymers are integral to the material selection for mechanical design, allowing engineers to tailor choices based on specific application requirements such as strength, thermal resistance, and cost efficiency.

Ceramics

In the context of material selection for mechanical design, ceramics offer exceptional thermal stability, high hardness, and remarkable wear resistance, though their inherent brittleness necessitates careful design consideration. For example, alumina (Al₂O₃) is a commonly used ceramic, featuring compressive strengths typically between 2000 and 4000 MPa, Young’s modulus in the range of 300 to 400 GPa, and a density of about 3800 kg/m³, which makes it ideal for applications such as cutting tools and high-temperature components.

Similarly, silicon carbide (SiC) is renowned for its high thermal conductivity and excellent resistance to thermal shock; it exhibits Young’s modulus of approximately 410 GPa, a density near 3200 kg/m³, and tensile strengths ranging from 300 to 600 MPa, rendering it suitable for abrasive environments and structural applications subjected to high thermal stresses.

Additionally, zirconia (ZrO₂), known for its transformation toughening, offers enhanced fracture toughness compared to many ceramics, with flexural strengths typically in the range of 900 to 1200 MPa and a density around 5600 kg/m³, which allows for improved resistance to crack propagation in demanding mechanical design scenarios. These detailed specifications highlight how ceramics are integral to material selection for mechanical design, providing engineers with critical data to match ceramic properties with the rigorous performance demands of various applications.

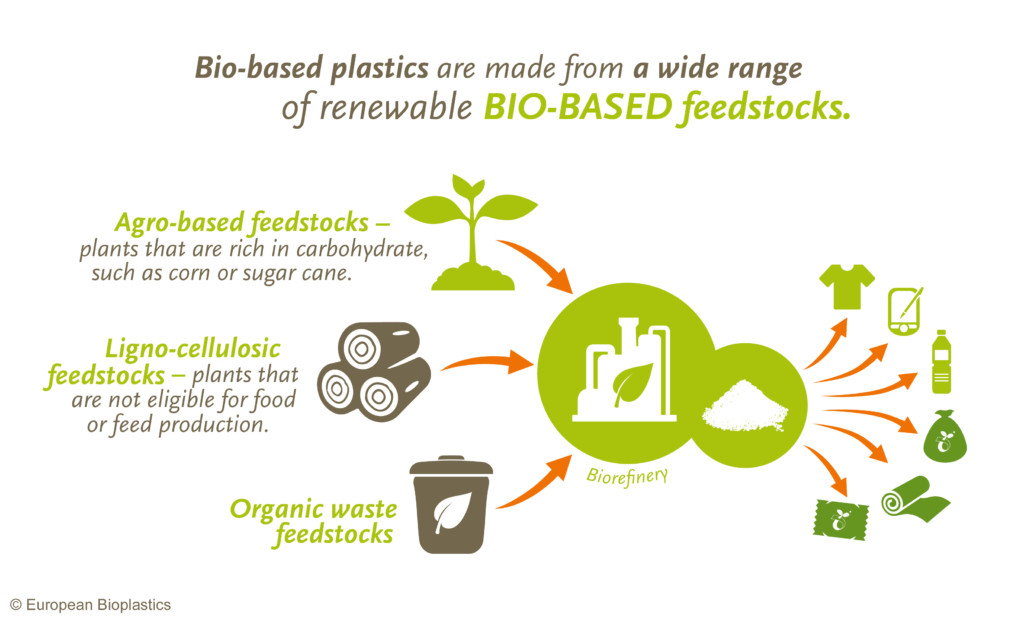

Bio-based materials

Material selection for mechanical design using bio-based materials is garnering increasing attention as sustainable alternatives that blend eco-friendliness with competitive mechanical performance. For instance, biopolymers such as polylactic acid (PLA) typically exhibit tensile strengths in the range of 50–70 MPa, Young’s modulus of approximately 3–4 GPa, and densities around 1240 kg/m³, making them suitable for non-critical load-bearing applications and rapid prototyping.

In addition, natural fiber composites—often reinforced with fibers like jute, hemp, or flax—offer tensile strengths ranging from 100 to 200 MPa and moduli between 5 and 15 GPa, with densities usually falling between 1200 and 1500 kg/m³; these composites not only provide improved specific strength and stiffness but also significantly reduce the environmental footprint compared to conventional synthetic materials.

The integration of bio-based materials in material selection for mechanical design is further bolstered by their inherent recyclability and lower embodied energy, factors that are becoming increasingly pivotal in sustainable engineering practices. By combining renewable resources with advanced processing techniques, bio-based materials are evolving to meet the rigorous performance demands of modern applications while addressing environmental sustainability and lifecycle concerns.

A Structured Framework for Material Selection

Step 1: Define Design Requirements & Constraints

The first step in a structured framework for material selection for mechanical design involves a detailed definition of design requirements and constraints that serve as the foundation for all subsequent decisions. In this initial phase, engineers begin by establishing clear performance criteria such as load-bearing capacity, weight limitations, and the ability to withstand thermal stresses; for example, a component in an automotive engine may need to support high cyclical loads while minimizing weight to improve fuel efficiency and simultaneously resist thermal expansion due to rapid temperature fluctuations.

Equally important is the consideration of economic constraints, including the overall cost of materials and manufacturing processes, as well as environmental constraints like the material’s carbon footprint, recyclability, and potential regulatory impacts on sustainability. By integrating these multifaceted criteria, the process of material selection for mechanical design becomes a balanced exercise that not only focuses on technical performance but also accounts for budgetary limits and environmental stewardship, ensuring that the selected material will meet both the immediate and long-term needs of the project.

Step 2: Identify Critical Material Properties

The second step in material selection for mechanical design involves identifying and prioritizing the critical material properties that will determine the success of the final product. At this stage, designers focus on key performance indicators such as specific strength—the ratio of tensile or yield strength to density—and specific modulus, which is the ratio of Young’s modulus to density.

These metrics enable engineers to assess how effectively a material can support loads relative to its weight, a factor of paramount importance in applications like aerospace and automotive design where every kilogram matters. For example, titanium alloys might exhibit a tensile strength of around 900 MPa and a density near 4500 kg/m³, resulting in a specific strength roughly in the range of 200 MPa·m³/kg, while aluminum alloys, with tensile strengths of approximately 300 MPa and densities of about 2700 kg/m³, typically offer a specific strength closer to 110 MPa·m³/kg.

Similarly, the specific modulus for titanium, given its Young modulus of about 110 GPa, can be significantly higher than that of aluminum, which has a modulus of around 69 GPa. In addition to these ratios, other properties such as fatigue resistance, thermal stability, and corrosion resistance are evaluated based on the operating environment of the component. By quantitatively analyzing these parameters, the process of material selection for mechanical design becomes a methodical evaluation that aligns material properties with the performance, economic, and environmental requirements defined in earlier steps.

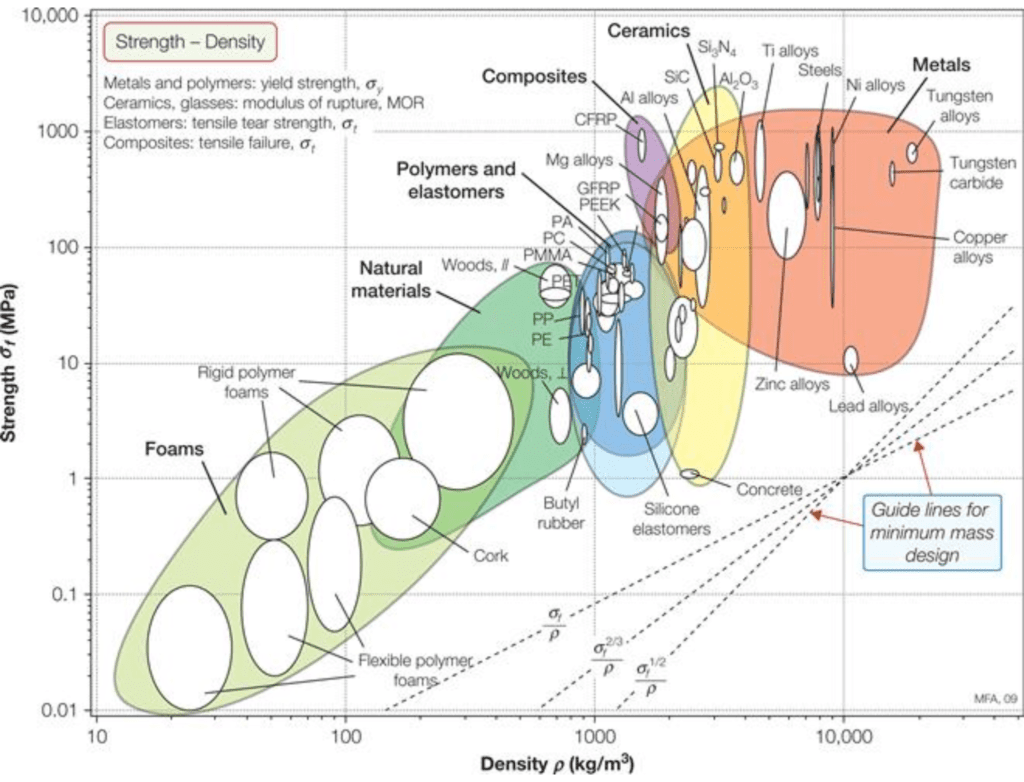

Step 3: Use Performance Indices & Ashby Charts

The third step in material selection for mechanical design involves the use of performance indices and Ashby charts to quantitatively evaluate and compare materials based on their mechanical properties relative to density. For example, when a design is dominated by tensile loading, the performance index is often defined as σ/ρ, where σ represents tensile strength and ρ is the material’s density.

This ratio provides insight into the material’s ability to carry loads without incurring excess weight. In applications dominated by bending, however, the performance index is typically expressed as √σ/ρ, which accounts for the fact that bending stresses are influenced not only by strength but also by stiffness and geometry, and it emphasizes the importance of a material’s modulus in relation to its density.

Ashby charts are graphical tools that plot these material properties on logarithmic scales, allowing engineers to visualize the performance indices across different material families. By plotting materials on these charts, designers can identify regions where specific materials—such as metals, polymers, ceramics, composites, or bio-based materials—exhibit superior performance according to the chosen index. For instance, if the application is tension-dominated, materials that lie above the line defined by σ/ρ on the Ashby chart will be more favorable.

This visual comparison not only simplifies the process of screening materials but also helps in understanding trade-offs between competing properties such as strength, stiffness, and weight. Using performance indices and Ashby charts in the context of material selection for mechanical design allows for a systematic and informed approach to selecting the most suitable material for a given application.

Step 4: Iterative Evaluation and Trade-off Analysis

The fourth step in material selection for mechanical design centers on iterative evaluation and trade-off analysis, where engineers must balance technical performance with cost and sustainability. In this stage, the chosen material is continuously assessed against evolving design requirements, economic considerations, and environmental impacts, ensuring that the selected option not only meets the necessary performance indices—such as specific strength and stiffness—but also aligns with budgetary constraints and sustainable practices. For instance, a designer might compare a high-performance titanium alloy with a slightly lower-cost aluminum alloy, considering factors like lifecycle cost, recyclability, and energy efficiency during production.

This process often incorporates interactive checkpoints—such as “What would you choose?” quiz sections—where engineers and students are prompted to evaluate real-world scenarios, weigh the benefits and drawbacks of each material, and make informed decisions based on quantitative data and qualitative insights. These iterative evaluations help refine the material selection for mechanical design by highlighting trade-offs between superior mechanical properties and associated costs, as well as the long-term benefits of sustainability, ultimately guiding the decision-making process toward the most balanced and optimal material solution.

Advanced Strategies and Emerging Trends

Integrating Eco-Design and Lifecycle Analysis

Integrating eco-design and lifecycle analysis into material selection for mechanical design requires a detailed assessment of environmental factors such as recyclability, energy consumption, and the overall CO₂ footprint of a material. In this advanced strategy, engineers examine the complete life cycle of a material—from raw material extraction and manufacturing through use and eventual end-of-life disposal or recycling—to quantify its environmental impact. For example, primary production of aluminum can emit approximately 12–17 kg CO₂ per kg, yet its high recyclability can reduce overall emissions by up to 95% when recycled material is utilized.

Similarly, comparing traditional polymers with emerging biopolymers, the latter often demonstrate a lower carbon footprint; some biopolymers may result in as little as 2–4 kg CO₂ per kg, provided that sustainable processing methods are employed. These metrics enable designers to factor environmental sustainability into material selection for mechanical design, ensuring that the chosen materials not only meet performance and cost criteria but also align with eco-design principles. By integrating such quantitative environmental data into decision-making, engineers can optimize both the technical and ecological aspects of their designs.

Leveraging Digital Tools and Computational Methods

Leveraging digital tools and computational methods has revolutionized the process of material selection for mechanical design, enabling engineers to quickly and accurately identify candidate materials and verify their suitability through advanced simulation techniques. Modern material selection software—such as CES EduPack and Granta Design—integrates extensive databases with AI-driven algorithms, allowing designers to filter and compare materials based on critical properties like specific strength, thermal stability, and recyclability. These digital platforms not only facilitate rapid screening through interactive Ashby charts and performance indices but also provide up-to-date data that reflects the latest industry standards.

In parallel, simulation tools like Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) play a crucial role in verifying design choices. For instance, after selecting a candidate material for a load-bearing component, an engineer might employ FEA software such as ANSYS to analyze stress distribution and deformation under operational loads, ensuring that the material meets all performance criteria. Similarly, CFD tools like ANSYS Fluent or COMSOL Multiphysics are used to simulate fluid flow and thermal performance around the component, providing insights into cooling efficiency and potential hot spots. Together, these digital tools form a cohesive ecosystem that supports material selection for mechanical design by merging data-driven decision-making with rigorous simulation-based validation.

The Impact of Additive Manufacturing and Topological Optimization

In material selection for mechanical design, the advent of additive manufacturing and topological optimization is redefining material requirements by enabling the creation of intricate, optimized geometries that were once unattainable through traditional manufacturing methods. Advanced 3D printing technologies allow engineers to fabricate components with complex lattice structures, internal voids, and variable density distributions that optimize the use of material, thereby reducing weight while maintaining or even enhancing strength and stiffness. Topological optimization algorithms further refine these designs by iteratively removing non-critical material, focusing on the areas that contribute most to mechanical performance, which transforms the conventional criteria used in material selection.

This new paradigm means that the material’s performance is evaluated not just by its bulk properties—such as tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and density—but also by its behavior when configured into innovative, non-homogeneous architectures. For instance, a material that might seem less competitive in a conventional design can exhibit superior performance when its microstructure is tailored through additive manufacturing processes, enabling enhanced energy absorption and load distribution. Simulation tools such as Finite Element Analysis (FEA) are then employed to validate these optimized designs under realistic loading conditions, ensuring that the selected material meets the stringent demands of both performance and sustainability in the final application.

Exploring Smart and Adaptive Materials

Emerging materials, like shape-memory alloys and bio-inspired composites, highlight an intriguing trend in material selection for mechanical design. Shape-memory alloys, for instance, exhibit unique transformation temperatures, such as NiTi’s approximately 55°C.

Given the increasing popularity of smart and adaptive materials, shape-memory alloys (SMAs) like Nitinol stand out due to their shape recovery and actuation abilities, making them ideal for applications requiring self-healing and actuation capabilities.

Exploring smart and adaptive materials represents an exciting frontier in material selection for mechanical design, where emerging materials such as shape-memory alloys and bio-inspired composites are redefining how components respond to external stimuli. For example, shape-memory alloys (SMAs) like Nitinol—a nickel-titanium alloy—are renowned for their ability to recover predefined shapes when heated above their transformation temperature, typically around 55°C, and can exhibit recoverable strains up to 8–10% with tensile strengths ranging from 800 to 1200 MPa.

These properties make SMAs ideal for applications that require actuation, vibration damping, or self-healing capabilities. In parallel, bio-inspired composites, which mimic the intricate hierarchical structures found in natural materials such as nacre or bone, combine organic and inorganic phases to achieve exceptional toughness and strength; engineered bio-composites can offer tensile strengths between 100 and 200 MPa and fracture toughness values in the range of 10–20 MPa·m^0.5 while maintaining low densities.

These performance metrics are crucial as they expand the traditional criteria—such as specific strength and modulus—used in material selection for mechanical design, enabling the development of systems that can adapt dynamically to changing operational conditions without sacrificing structural integrity or increasing weight. The integration of these smart materials into design strategies not only enhances functionality and durability but also broadens the spectrum of trade-offs considered during the selection process, ultimately pushing the boundaries of innovation in mechanical design.

Interactive Case Study: Material Selection for a Lightweight Structural Beam

Problem Statement and Design Brief

In this interactive case study focused on material selection for mechanical design, the problem statement and design brief center on a lightweight structural beam intended to support a defined set of mechanical and environmental loads while adhering to strict cost constraints. The beam is required to support a uniformly distributed load of 5 kN/m along its length, along with concentrated loads at specific intervals that simulate realistic operational conditions. Additionally, the design must account for variable environmental factors, including temperature fluctuations ranging from -20°C to 80°C and moderate humidity levels, which could affect material properties such as thermal expansion and corrosion resistance.

Economic constraints are equally critical, with the project budget limited to materials costing no more than $3 per kilogram and a target lifecycle cost that emphasizes not only initial procurement but also long-term maintenance and recyclability. This comprehensive design brief establishes a rigorous framework for evaluating candidate materials, ensuring that the chosen material optimally balances load-bearing capacity, environmental resilience, and cost efficiency in the context of material selection for mechanical design.

Step-by-Step Application of the Framework

The next step in our step-by-step application of the framework for material selection for mechanical design involves the systematic determination of key performance indices and the utilization of Ashby charts to filter and narrow down candidate materials. Initially, designers identify and calculate performance indices tailored to the specific loading conditions of the structural beam; for example, for tensile-dominated applications, the performance index is often defined as the ratio of tensile strength (σ) to density (ρ), while for bending-dominated scenarios, it is more appropriate to use the index √σ/ρ.

These indices offer a quantitative measure of a material’s efficiency in carrying loads relative to its weight and provide a clear metric for comparing disparate materials. Once the appropriate performance indices are established, engineers turn to Ashby charts—graphical representations that plot material properties on logarithmic scales—to visually compare candidate materials. By overlaying the performance index lines onto the Ashby charts, designers can quickly identify which materials fall within the desired performance envelope.

For example, materials that lie above the threshold line for σ/ρ in a tension-dominated case are considered strong candidates, while those below the line are eliminated from further consideration. This visual and quantitative analysis ensures that the material selection for mechanical design not only meets the technical performance criteria but also aligns with the design’s weight and cost constraints. The iterative process of calculating indices and consulting Ashby charts provides an effective method for screening materials, ultimately leading to a shortlist of candidates that are best suited to satisfy the design requirements.

Analysis of Trade-offs and Final Recommendation

In analyzing the trade-offs for our lightweight structural beam, several factors emerge that guide material selection for mechanical design. Titanium alloys, for example, offer outstanding specific strength and stiffness, making them highly attractive for critical load-bearing applications; however, their high cost and challenging processing may render them less suitable when budget constraints are tight. In contrast, aluminum alloys strike a balance by providing moderate tensile strengths (approximately 290–310 MPa) and low density (around 2700 kg/m³), resulting in a favorable strength-to-weight ratio at a significantly lower cost.

Additionally, aluminum’s recyclability and lower embodied energy further enhance its appeal under environmental sustainability criteria. While advanced composites can be engineered to surpass metals in terms of specific performance, their anisotropic properties and the complexity involved in manufacturing often introduce uncertainties that complicate their deployment in standardized designs. Consequently, the trade-off analysis—considering technical performance, economic limitations, and environmental impact—indicates that aluminum alloys may be the most pragmatic choice for this design scenario, effectively balancing multiple criteria within the context of material selection for mechanical design.

Reflection and Reader Questions

In material selection for mechanical design, it is important to reflect on the choices made and consider how alternative scenarios might affect overall performance and sustainability. For instance, how would the selection criteria change if the design were required to operate in an extreme thermal environment or if the cost constraints were significantly relaxed? Could a high-performance titanium alloy, despite its expense, be justified for a safety-critical component, or might a hybrid composite approach offer a better compromise between weight and cost?

Additionally, what impact might emerging eco-design metrics—such as reduced CO₂ footprint and enhanced recyclability—have on traditional material choices? These questions encourage readers to critically evaluate not only the quantitative performance indices but also the broader implications of material selection for mechanical design, opening the door to innovative approaches and interdisciplinary trade-offs that can lead to more optimized, sustainable solutions.

Integrating Material Selection into the Overall Mechanical Design Process

Collaboration Between Design, Manufacturing, and Sustainability Teams

In material selection for mechanical design, collaboration between design, manufacturing, and sustainability teams is essential for achieving an optimized and holistic design outcome. When design engineers and manufacturing specialists work together, they can align the theoretical performance indices—such as specific strength and modulus—with practical production constraints like machinability, weldability, and tolerances. This interdisciplinary input ensures that materials not only meet the rigorous technical requirements but are also feasible for large-scale production and cost-effective processing. Moreover, sustainability teams contribute crucial insights into environmental impacts by assessing lifecycle analyses, recyclability, and the overall CO₂ footprint of candidate materials.

For example, while a high-performance alloy might excel in mechanical properties, its elevated production costs and environmental burdens could prompt the team to consider alternative materials or hybrid composites that balance performance with eco-design principles. The integration of diverse perspectives leads to a more informed material selection for mechanical design, where trade-offs between technical performance, manufacturing practicality, and sustainability are systematically addressed, ultimately fostering innovation and robust product development.

Feedback Loops: Iteration and Validation

Feedback loops in material selection for mechanical design play a critical role in ensuring that theoretical material properties and simulation results translate effectively into real-world performance. After an initial screening based on performance indices and Ashby charts, prototypes are fabricated using the selected materials and then subjected to rigorous testing regimes, such as static load testing, fatigue analysis, and thermal cycling. These tests provide quantitative data on factors like yield strength, elongation, and durability under operational conditions, which may reveal discrepancies between expected and actual performance. For example, a material that appeared optimal in simulation might exhibit unforeseen issues such as rapid degradation under cyclic loading or sensitivity to temperature fluctuations.

The feedback obtained from these experiments enables engineers to iterate on the design by refining simulation models, revisiting material properties, and even considering alternative candidates that better align with the design’s real-world demands. This iterative process of prototyping, testing, and validation ensures that the material selection for mechanical design is continually optimized, ultimately reducing risk, enhancing reliability, and aligning with both cost and sustainability targets.

Documentation and Continuous Learning

In the context of material selection for mechanical design, documentation, and continuous learning are integral to ensure that the knowledge gained through each project iteration is effectively captured and disseminated across the organization. Engineers are encouraged to meticulously record lessons learned from each phase of material selection—from initial simulations and prototype testing to final performance validation. This documentation includes detailed data on material performance, observed discrepancies between predicted and actual behavior, and insights on processing challenges, which are then integrated into internal databases and shared within cross-functional teams.

Continuous learning initiatives, such as regular training sessions and updates to material property databases, enable teams to stay current with the latest research findings, technological advancements, and eco-design methodologies. By fostering a culture of knowledge sharing and systematic record-keeping, organizations can refine their material selection for mechanical design processes over time, leading to more robust, efficient, and sustainable engineering solutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the framework for material selection for mechanical design involves a systematic step-by-step process that begins with defining precise design requirements and constraints, identifying critical material properties through quantitative performance indices, and utilizing visual tools such as Ashby charts to narrow down candidate materials. Trade-off analysis plays a pivotal role in balancing technical performance with economic and environmental factors, while advanced strategies—including digital tools, additive manufacturing, and the integration of smart materials—further refine the decision-making process. This multidisciplinary approach enables engineers to evaluate competing material options thoroughly and make informed decisions that optimize both performance and sustainability.

The importance of informed material selection cannot be overstated. A systematic and multidisciplinary methodology not only ensures that a design meets stringent mechanical and environmental demands but also fosters innovation by continuously integrating emerging technologies and sustainability principles. By rigorously evaluating performance indices and incorporating real-world feedback loops, engineers can reduce risks and drive efficiency throughout the design process. The adoption of digital tools and simulation methods further supports this process by providing real-time data and predictive insights, ultimately resulting in more robust and cost-effective solutions.

For those interested in further exploration of these topics, several resources are recommended. Textbooks such as “Materials Selection in Mechanical Design” by Michael Ashby and the ASM Handbooks provide a solid theoretical foundation and practical guidelines. Online courses and platforms like Coursera, edX, and MIT OpenCourseWare offer in-depth modules on material science and mechanical design. Additionally, software tools such as CES EduPack and Granta Design serve as excellent digital resources for real-world material selection, while industry publications and research journals provide ongoing updates on the latest advancements in sustainable and smart materials.

1 Comment

Thanks for the content.